At the time of the Black Death in the 14th and 15th centuries, Italians thought pottery was unhygienic. This lead to the destruction of much of the early pottery dating from the 13th century to the early 15th century. ( Pottery in India was for a very long period thought to be unclean and this is probably why India produced so few pots and metal was the preferred material.) These wares seldom had charm and usually compared unfavourably with the contemporary and earlier wares produced in Islamic countries. Up to about 1420 the decoration consisted mostly of geometric motifs that sometimes incorporated stylised animals. This very early Italian pottery was influenced by imports into Southern Italy from Islamic North Africa that commenced about 1200.

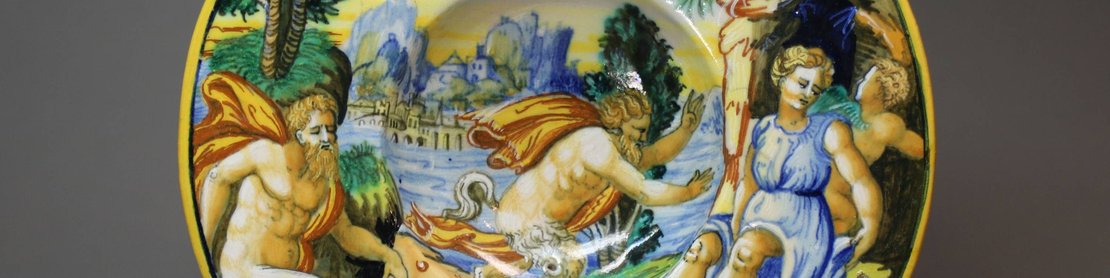

The best Italian maiolica was produced approximately between 1440 and 1540; before 1440 the decoration was too primitive and after 1540 the products of most factories were in decline, the decoration was losing its raw medieval dynamism and strength. It is particularly the albarelli that convey the magic of the early Renaissance especially those made in the second half of the 15th century. From 1520 onwards there was a tendency for the decoration to become more detailed and sophisticated and it lost some of its dramatic quality in the process. After about 1500 designs were often taken from engravings. The visual rhythm became gentler. There are, of course, exceptions to these generalisations.

In the late 15th century Italian maiolica (an Italian corruption of Majorca) was influenced by Moorish Spain, which traded with Italy through Florence, and subsequently by Greek and Roman art. Most of the very early wares were produced in Tuscany and Umbria at factories in Orvieto, Perugio and Florence. Primarily, Italian pottery produced before 1350 had a lead glaze. In the 13th, 14th centuries and earlier part of the 15th century, the only colours used were green and manganese/purple, respectively derived from oxides of copper and manganese, and subsequently a dark cobalt blue. By the end of the 15th century the colour range was widened and consisted of blue from cobalt, green from copper, yellow from antimony, orange from antimony and iron, and purple and brown from manganese. At an early date, red was a difficult colour to achieve and often turned out to be more of a sealing wax colour than a true red.

Italian maiolica wares were first produced about 1350. They had a glaze that was composed of a lead oxide opacified with tin oxide combined with a silicate of potash. The decoration was applied to the dried glaze which was porous and demanded accurate painting, errors could not be later rectified; consequently there is a spontaneity and rhythm to the painting which is peculiar to this medium. Once fired, the colours were permanently fixed and are seen now as they were seen hundreds of years ago.

Many of the finer early pieces of antique Italian maiolica had a second coating of a lead glaze, known as coperta, before the second firing. This improved the quality of the colours and appearance of the surface. The coperta glaze was composed of lead oxide combined with sand, potash and salt.

Sgraffiato wares, inspired by Near Eastern examples, were introduced in the 16th century. These used a lead glaze. The unfired dark biscuit body of a piece was dipped in a white slip of pipe clay mixed with water. It then received its first firing. Designs were then engraved with a pointed tool made of wood or iron. Once the engraving was complete a lead glaze was applied and a second firing took place. In some cases further decoration was painted on using underglaze pigments before the final firing. This decoration was some times applied to areas where the slip had been cut away to reveal the dark body beneath.

Why at a particular time in their history did certain countries produce fantastic pottery such as Italian maiolica? Were there common cultural circumstances peculiar to all these times and countries; such as inspirational parallel art forms, a demand from a cultivated and prosperous section of society and some stimulating foreign influences? English delft was initiated in the 16th century by migrant Dutch potters. It was at its best in the second half of the 17th century; when it was simply decorated and in some cases possessed unrivalled charm, but at that time England was not producing any other art of particular merit. In Turkey, pottery reached its peak in the late 15th century and in Spain pottery peaked in the late 14th and 15th centuries. Under certain circumstances maybe this medium encourages the inner most cultural mind-set to express itself. Antique pottery at its best is certainly charming and very atmospheric.

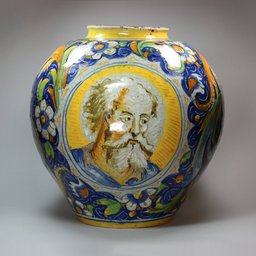

Gubbio is most famous for its maiolica lustre wares which no doubt were created a result of the Hispano-Moresque imported from Valencia in the 15th century. Silver and copper were responsible for the lustre on early pottery and in the case of Gubbio a magical ruby lustre was obtained by the use of copper oxide in the last firing in which brushwood was burnt towards the end of this firing.

These opening comments on antique Italian maiolica are to be followed by some further articles on the various major Italian pottery factories including Gubbio,Urbino, Venice, Castel Durante, Sienna and Caltigerone.

Museum Collections of Antique Italian Maiolica

Victoria and Albert Museum has a very large collection of Italian Maiolica on the 6th floor

Wallace Collection small collection of Italian Maiolica but with some fine examples